It’s been more than 20 years since I studied First World War fiction in sixth form college. It remains some of my favourite reading and has dominated my book consumption of late, so here’s a run-through of my adventures in this very challenging area of literature and history.

My family and the First World War

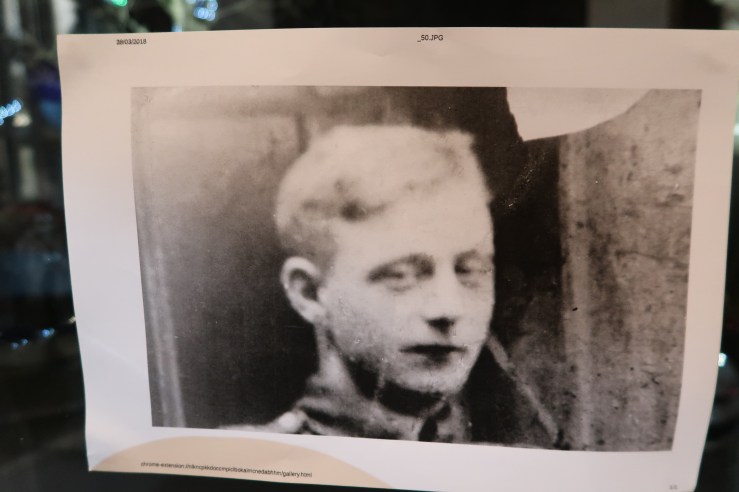

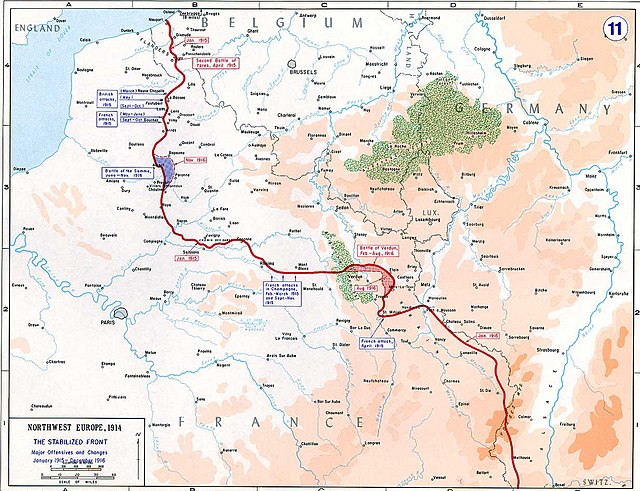

The face above is that of my great-grandfather Wilfred Hill (1896-1961). Here he is posing in his British army uniform some time around 1914 as he prepared to go to join the First World War (WWI). Both my paternal great-grandfathers served in WWI and both of them survived. One was at Ypres, the other at the Somme, both battles renowned for the conditions experienced by soldiers and the extreme loss of life.

At the Battle of Ypres there were 76,000 deaths.

On the first day of the Battle of the Somme there were nearly 20,000 deaths of British soldiers.

I don’t know much about my great-grandfather Wilfred’s stint, but I do know he was a runner and may have been rescued by Canadian soldiers after being buried alive in a shell-blast.

First World War literature

At A-level (aged 16-19) I studied the war poets Wilfried Owen and Rupert Brooke, and the more contemporary novels Birdsong (1993) by Sebastian Faulks and Regeneration (1991) by Pat Barker.

I found Birdsong ‘unputdownable’, but Regeneration a bit more difficult to love at the time.

The poetry has not really stayed with me, possibly because it is so tragic, Wilfred Owen being killed so late in the war. Part three of Barker’s Regeneration trilogy – The Ghost Road (1995) – dramatises Owen’s death, what I felt to be the best of the three novels. It also won the Booker Prize in 1995.

Another WWI novel that really captured my late-teenage mind was the Ice Cream War (1982) by William Boyd, telling the story of life in Africa while the British and German empires battled one another for territory. It began to reveal to me the complexity of empire, war and the relationships between the people mixing in those places.

“They didn’t talk about it”

My great-grandfather Wilfred was 22 when the war ended, but he had probably lived many lives over in that four years.

When I spoke to my dad about his grandfathers’ roles in that war, he said they didn’t talk about it. His maternal grandfather, Charles (born 1895), didn’t say much at all by the sounds of it! The issue of WWI veterans not talking about the war or the difficulty integrating into society during and after the war is a major theme of WWI literature, such was the brutality of it all. I’ve read about it in Regeneration, Birdsong, and the German novel The Way Back (1931) by Erich Maria Remarque.

J.L. Carr’s A Month in the Country (1980) tells the story of a WWI veteran who moves to a Yorkshire village to restore a church mural, post-war. The story expresses some of the social issues found in rural village life, between those who had served and those who had remained at home, not least the difficulty of finding love again.

Returning to the WWI novel

In 2024 I enjoyed a rich seam of fiction, mainly WWI literature, including the Pat Barker trilogy Life Class (2007), Toby’s Room (2012), and Noonday (2015). Looking at my reading list from last year, it didn’t include a single ‘nature writing’ book, which may surprise some readers of this blog. Instead my list is comprised almost completely of novels about WWI.

I wonder why that is. I remain staunchly anti-war (but aware of the need for self-defence) in my personal outlook on world events. Perhaps the wars in Ukraine, Gaza, and Sudan have me trying to understand why these things happen and the impact they have on people swept up by them. Perhaps I am preparing myself for what Trump’s election means for Europe, and the potential selling-out of Ukraine, and thus Europe, by his inexplicable cosying up to Putin, a war criminal.

Non-British perspectives

During my university years my dad handed me his copy of The Good Soldier Svejk (1923), a satirical account of a Czech soldier serving the Austro-Hungarian Empire in WWI, against the French and British forces. It is one of the few books that has made me laugh out loud, not something you will really find in British WWI lit. The illustration above should offer you a sense of it.

Offering an Irish perspective, Sebastian Barry has two exceptional novels which cover this terrible period in history.

The brilliant A Long Long Way (2005) by Barry includes elements of the Irish ‘Easter Rising’, which helped me to understand how the two conflicts were interlaced, and how much WWI was a war of collapsing European empires. Though not focused solely on the war, The Whereabouts of Eneas McNulty (1998) tells the story of a man’s life through both WWI and the Second World War (WWII). It’s one of the most enthralling novels I’ve read in a long time and has the feel of a classic to me.

At school we didn’t study All Quiet on the Western Front (Remarque, 1928) but in the autumn of 2024 I finally read it, having already seen the Netflix adaptation. As many will already know, it is an incredible novel. It is possibly the first WWI novel I’ve read from a German perspective, but the anti-war sentiments are universal. There is so much more that could be said about this novel. The Way Back is the follow-up, but I didn’t finish it because I was reaching my temporary limit for WWI reading.

Empires at War

Speaking of collapsing empires, Sathnam Sanghera’s non-fiction Empireland (2021) really is worth reading. I enjoyed it so much I then read Empireworld (2024), which is also excellent but heavy. It covers slavery in some detail, and it’s harrowing reading.

There is so much about our lives over here in Britain that can be better understood within the colonial context of the British Empire. I know that some can apparently feel quite unhappy about this being raised (not that I have actually met anyone who is), but Sanghera is not looking to goad or whip up division on the topic. I feel that he makes that point very well throughout, but you wonder how fair it is that he keeps having to say it.

In the south of England soldiers from the Indian regiments stayed in temporary hospitals at the Royal Pavillion in Brighton, and out on the heaths in what is now the New Forest National Park. This post on the University of Sussex blog goes into excellent visual and historical detail about the Indian contingent in Brighton.

Moving into 2025, I began the year reading David Olusoga’s The World’s War (2014). Olusoga is a WWI enthusiast, and this is one of the best books I’ve read on the subject. You may know David Olusoga from A House Through Time and his writing about the Bristol statue riots in 2020. He now is a Goalhanger podcaster with Sarah Churchwell on Journey Through Time. The World’s War helped me to understand just how vast WWI was at continuous landscape-scale.

WWI was the first time men of colour came to fight in European wars on European soil. This exposed the varying degrees of racism and white supremacy in each army, but perhaps went furthest in highlighting the seedlings of fascist ideology growing in pre-Nazi Germany. Olusoga ranks the fledgling American military as one of the worst – perhaps unsurprisingly – whereas the French military allowed men of colour to rise up the ranks and be treated with a greater degree of respect. That said, the violence experienced by black American military personnel in St. Nazaire left many questions, and the treatment of colonised Senegalese regiments in the French army echoes the worst of white supremacist imperialism.

Germany waged racist propaganda against the Allies and their black regiments during and after WWI. Olusoga makes the case for how this virulent strain of white supremacy provided the foundation for Hitler, with children born of relationships between white German women and black Allied soldiers being forcibly sterilised to ‘protect the white race’. We should all know by now that Hitler and his acolytes focused the national shame of losing WWI on a lack of racial purity, and we all know that it ended up at Auschwitz where 6million Jews were murdered, as well as many Roma, black, LGBT and disabled people.

One of the most shocking and appalling outcomes of the post-war (or inter-war) period was the wave of murders carried out against black American servicemen on their return from WWI. The worst excesses of white American, anti-black hate reared its head, leading to the brutal killing of decorated soldiers and their families on the streets of the United States. I didn’t know about this, and I felt sickened reading about it.

The summer of 1919 was known as the ‘Red Summer’. White American racists, including well known outfits like the Ku Klux Klan, felt that black Americans needed to be ‘put in their place’ after their achievements on the Western Front. What expresses the feral nature of this violence is how women and children seemed to be involved in these attacks and crimes, not merely men. Black men were lynched in their military uniforms.

Indeed, many of the issues I have witnessed in my lifetime arguably have echoes in the 1910s. Not least the rise of the far-right in Europe and white supremacy in America are obviously not new issues.

They’re just issues I thought society had learned from, having seen where these issues end up.

What can we learn from reading the First World War?

What I take from reading this wide array of fiction and non-fiction is that war is stupid, cruel and driven by greed. The suffering experienced by people during WWI is not something I feel I can comprehend, but the voices of the people who lived through it can teach us important lessons. Those lessons are that war is misery and wars of aggression, like Putin’s in Ukraine and now Netanyahu’s on the civilians of Gaza, should never happen. War destroys not just people and culture but landscapes and ecosystems humanity depends upon for a stable existence.

Do you have any recommendations? Please let me know in the comments.

Thanks for reading.