Innsbruck, Tyrol, Austria, June 2025

This is a longer post of the images I captured during a recent visit to Innsbruck in the Austrian Alps. We travelled to Innsbruck on a sleeper train from Amsterdam. It’s such a great experience and is significantly lower in carbon emissions compared with flying. If you consider the fact it’s travel and accommodation, as well as the ability to see so much more, it’s a better way to travel. We set off from London on the Friday morning, on an 11am train to Amsterdam, and by 19:00 we were on the sleeper and heading south-east towards Germany.

All that said, we booked a sleeper train from Brussels to Vienna on our honeymoon in 2024 and the train didn’t show up! So travelling by train needs flexibility and patience. I still think it’s worth it, for you as well as the climate.

The photos here are taken with my Olympus EM-1 MIII and TG-6 compact cameras, edited in Lightroom.

In Innsbruck

According to my Lonely Planet guide to Austria, Innsbruck was founded in the 1100s. The name basically means ‘bridge over the River Inn’, which splits the north from the south of the city. It’s an epic river, which was in full flow when we visited, probably bolstered by glacial melt from the surrounding mountains.

The colourful apartment buildings on the north side of the Inn (seen here at the bottom of the frame) are a sight to behold from the banks of the south side. It’s hard to appreciate how difficult it would been to build a bridge over a river of this size and power once upon a time. No wonder that when they did manage it, the whole place was named after it!

Innsbruck is a city of towers and spires. I don’t know how many were destroyed in the Second World War. As in Salzburg, I’m sure many were rebuilt. The tower seen in the last of the images above can be ascended for a small entry fee via a pair of spiral staircases. I have issues with heights, and I found this quite difficult. I was a bit ill at the time so that probably made it worse. The views from the tower are of course worth it if you can cope with the ascent.

These metal workings were prevalent in the Aldstadt. They’re nice to photograph, particularly against cloud where their colours come to life. I don’t know anything about them, but they seem to be an Austrian thing, and date back several hundred years.

The ‘Golden Roof’ (Goldenes Dachl) was the main draw for tourists (I had read about it but wasn’t thinking of it when we found it). It was created in 1500 and was used by Habsburg royalty to purvey the scenes below.

On the 700-year-old Maria Theresa Street (Maria-Theresien-Straße) you can see frescoes depicting Maria, the only female ruler of the Habsburg Empire between 1740-1780. There’s a good summary of the history of this ancient street on the Innsbruck tourism website.

There are lots of interesting frescoes around the Aldstadt (Old Town) in Innsbruck, some originally painted as much as 400 years ago.

The Hofburg or Imperial Palace encloses the Aldstadt. Dating to the 1400s, it is considered one of the three most important Austrian buildings (according to Wikipedia). There were a number of weddings happening when we arrived on the Saturday morning. In the final image of the set here you can see one woman in her wedding dress being escorted somewhere – presumably before the ceremony.

Innsbruck Cathedral (Dom zu St. Jakob) sits close to the Inn. These were taken with my 9mm f1.7 wide angle lens, which is a thing of beauty.

Now it’s time to head into the hills (by cable car)!

Above Innsbruck

You can travel to the ‘Top of Innsbruck‘ via the Nordkette cable car. It’s a good option for high level walking and to get a sense of the grandeur of the Alps around Innsbruck.

The first cable car is the Hungerburgbahn which drops you at Hungerburg – and no, that’s not a marketing ploy for a restaurant. Here you change for a cable car to take you up to Seegrube.

It was mid-June and the views from Seegrube were dimmed by the thick haze that rested across the mountains. I have edited these photos to draw out the shapes and colours of the peaks as best I can without ruining them.

The road winds down to Hungerburg. In the middle-distance the Inn cuts through the city.

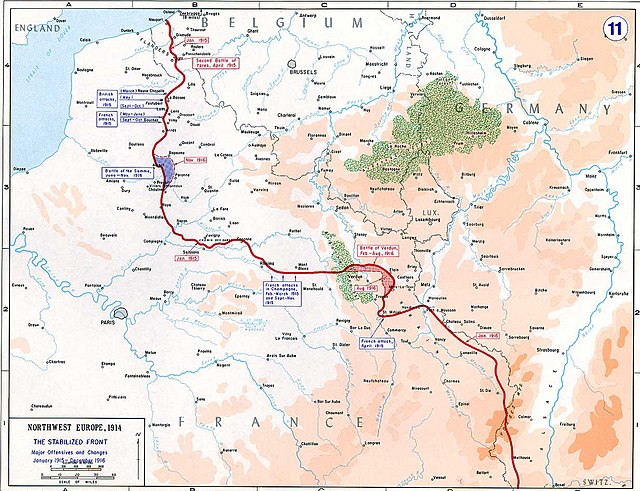

This is looking south towards the Italian Alps. Brutal warfare took place here between the Austro-Hungarian/German army, and newly-founded Italian army in the First World War. I didn’t know anything about this element of WWI (known as the White War) until my uncle told me about it. It was only after visiting Innsbruck that I realised the setting for the fighting was not far from here. Over 150,000 soldiers died in those battles, mostly due to disease or the extreme cold.

From Seegrube you can take a final cable car (not absolutely final!) to Hafelekarspitze (2,256m at the point of stepping off the cable car).

There are plenty of paths to take.

Looking back down from the Hafelekarspitze terminus. Unfortunately I wasn’t well enough to crouch down for any macro photos of the alpine plants, but there weren’t actually that many here because of the erosion.

Heading over a mound (sounds like a terrible understatement) you arrive at breathtaking views into the Alps. The sudden rearing up of these vast rocky peaks almost knocked me sideways. The cable car fees are worth it for these views.

Some snow was still lingering among the clefts in the limestone.

I love the streaks in the vegetation where water finds its quickest way down of the tops of the peaks. And then there’s just a random chunk of woodland there like the arm of a velvet green divan.

The reality of the space behind the camera – lots of limestone, hundreds of people, and a lot of erosion (of which I was obviously contributing to!).

Leaving Innsbruck

We left Innsbruck on a train to Salzburg, passing the peaks of the Karwendel Alps which lead eventually to Bavaria in Germany. I love travelling on Austrian trains, especially in the Alps. I don’t read a word of a book because the views are so amazing, and you can order food if you’re in first class, which is so much more affordable than in the UK.

I like to use my compact camera on these journeys and just snap photos randomly at the window without considering framing, or worrying to much about what the frame will capture. In the image above there’s what looks like a haybarn in the Inn valley, where the grass will be grown for either feeding animals or some kind of biomass.

Thanks for reading.