Merlin Sheldrake’s Entangled Life has been sitting on my bookshelf for well over a year. It might even be two years. It almost certainly has fungal spores on it, probably mould.

I knew it was going to be an excellent book that contains huge amounts of fascinating info about the fungal kingdom because I’d read the first 50 pages. Alas, I couldn’t find the mental space to take it all in. The reviews have also been almost universally positive, from a broad cross section of readers. This includes people new to the study of fungi and those who are more experienced.

Recently I have had a bit more of that required mental space, after a year of being swamped. I’ve now read the book and It. Does. Not. Disappoint. You get the impression that Sheldrake could write books for the rest of his days focusing on one of the themes chaptered each time, such is the depth of each subject.

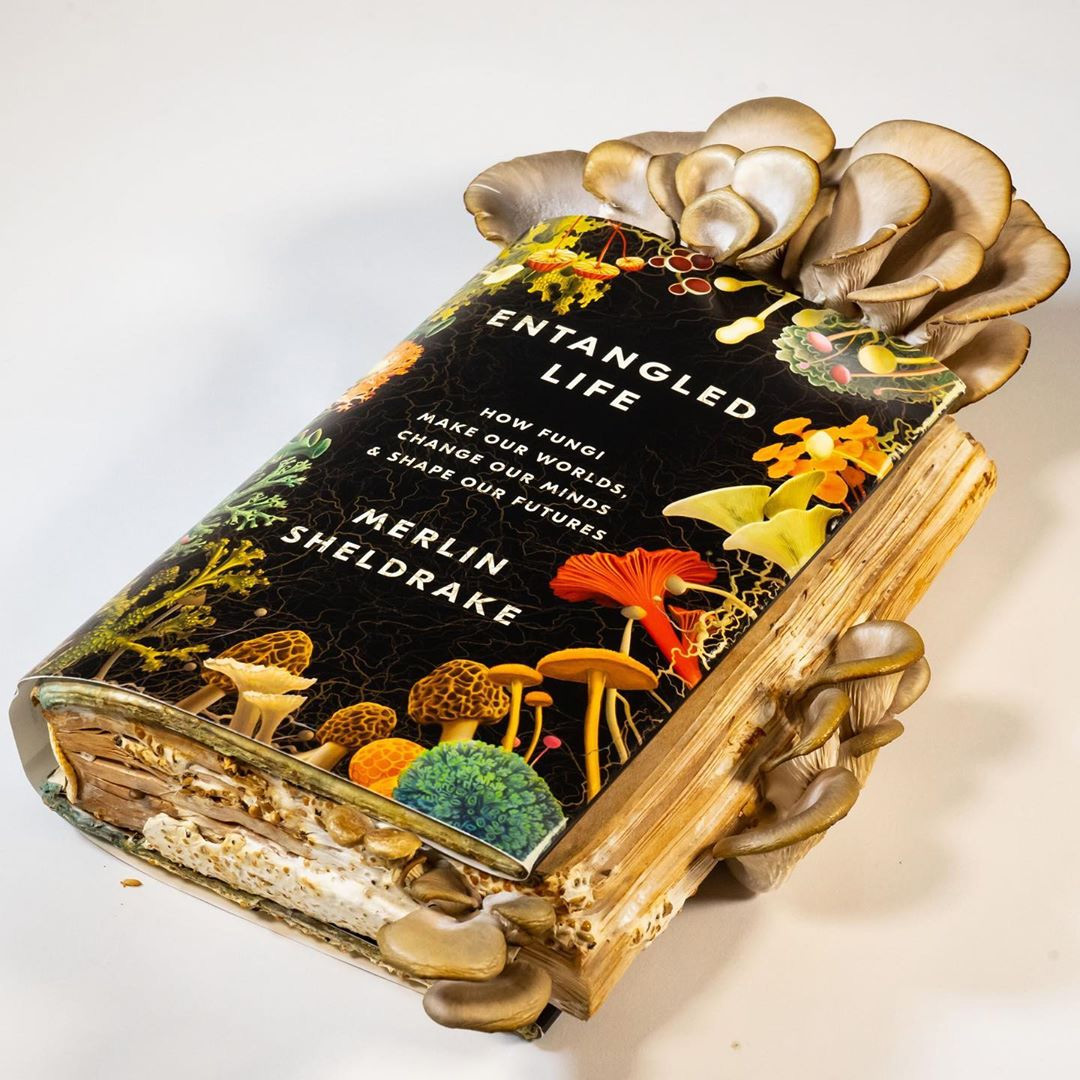

It’s the kind of book fungi have been waiting for to tell their stories, as the meme below so totes hilariously illustrates:

I read it with the sense that Sheldrake was using his extensive knowledge and research into fungi to campaign for a better appreciation before it is too late. That said, there isn’t the overarching doom narrative of a lot of nature conservation messaging, more a sense of awe regarding how little we know and have the potential to uncover. This is a book about hope and new possibilities, while understanding some of our planet’s oldest secrets.

It becomes clear halfway through the book that fungi are not an add-on to plants, they are the reason that we even have those bright green things as they are today. It’s a point I often labour at public events and to people not yet convinced by the importance of wilder, species-rich landscapes – without fungi we would not exist.

Suzanne Simard is namechecked as the founder of the ‘Wood Wide Web’, showing that plants actually behave far more communally and that fungi are the lifeblood of the mineral and resource exchange that builds the world we have evolved in. Sheldrake also features several other female academics, a welcome move in a community dominated by middle-class, white male perspectives and privileges. Simard’s book, Finding the Mother Tree is an absolute must-read and is included as a hugely important character in this narrative.

🍄

The more I read about fungi, especially in Sheldrake’s writing, it just makes me think how little we know about anything. We spend a lot of time warring with one another during such short windows of life, we should be using that time to learn more about the incredible world we live in. For example, fungi were only given their own kingdom in 1969, previously just lumped in with plants or as flora. Now there are calls to speak of flora, fauna and funga. Cowafunga, dudes!

Perhaps because most fungi are almost all out of sight (endophytes live within the tissue of plants, rather than producing charismatic fruiting bodies like fly agaric, above ground). Endophytes thus remain forever out of mind. In this sense, our innate human biases (sight) are restricting our ability to conserve vital biodiversity in the form of fungal diversity in soils and other ecosystems. There is evidence about how more charismatic wildlife receive the majority of conservation funding.

Some of the facts on display in Entagled Life will blow you away. Consider that lichens may not be what we think they are, and that some fungi used to ‘lichenise’ but no longer do. The relationships between plants, fungi, algae and bacteria are not necessarily fundamental but more opportunistic. Tree species that are more ‘promiscuous’ are more likely to have found greater dominance over larger areas because they can link up with fungi as they go. The connections trees have with fungi have shaped the landscapes of today.

Further to this, fungi are so biologically complex that it may not be possible to truly name them scientifically as distinct species!

Fungi are able to break down rocks, as they will have done hundreds of millions of years ago to create the first soils and thus stable ecosystems for us humans to evolve in.

Then there are the theories that humans developed complex languages through the brain development spurred on by the ingestion of psylocibin (the hallucinogenic chemical found in some fungi) and other ‘magic’ mushrooms. That remains unproven, as Sheldrake responsibly underlines. But the idea is brilliant and makes life seem so random.

I also was unaware that LSD is derived from the fungus ergot, and ergot infection of people back in mediaeval times may be the reason they ‘danced for days’. Now certain Berlin 24-hour nightclubs make more sense, though they’re way past my bedtime.

Fungamentally this is a book that everyone, from fungi enthusiast to someone just looking to know a little bit more, can get a lot from. It’s written in a very lucid and engaging way, though bear in mind it does take a scientific and methodical approach to its subjects. After the glut of recent nature writing where man-encounters-divine-nature-for-the-first-time, usually in search of one species, that may be just what the mycologist ordered. That said, do species even exist? You have to wonder what Sheldrake will do next with the information he has to share.

Thanks for reading.

Latest from the Blog

First ichneumon wasp of 2024 🐝

You know it’s spring when the bees and things start getting trapped indoors again. I visited my mum on Easter Sunday and her kitchen (which has lots of windows) turned into a veritable insect survey trap. Not just the ‘horrible flies’ she pointed out, but this lovely ichneumon wasp which I rescued with a glass…

First solitary bees of 2024 🐝

Four years ago I was starting a weekly Macro Monday photoblog as we entered into the Covid-19 restrictions. Now I reflect on how that extra time helped me to post more regularly on here, and just how hard I find that now in the post-pandemic lifescape. I’ve not got into macro mode proper yet this…

Sussex Weald: eagles at Pulborough

Pulborough Brooks, West Sussex, February 2024 Looking out over the Brooks, two dark bird-shapes soar against the faint outline of the South Downs. Below them are green conifers and leafless oaks. Buzzards, I think. A woman approaches me from behind and stands to the side of me. ‘Dude,’ she says. ‘There’re eagles out there!’. I…