Following on from part one of my recent trip to Dartmoor National Park in south-west England, it’s now time for part two. You can read part one here.

This was another day chock-full with mushrooms. It began well with a nice indicator of mushroom season when we found a gathering of clouded funnel on a roadside verge. This is a fairly common mushroom that can usually be identified by its size and the clouded tops. My boot is here for scale, obviously.

You can see how happy fungi are in the wet and wild landscape of Dartmoor by the presence of moisture loving organisms like these cladonia cup lichens. You can read some of my lichen posts here.

We were just on the edge of the National Park. Dartmoor’s logo is based on the famous Dartmoor pony, a semi-wild(?) species that has been running amok on the moor for thousands of years.

Dartmoor on an autumn morning. The silver birch with yellow leaves is one of the highlights of autumn, especially when the light catches the leaves.

On top of a wood ant’s nest there were two mushrooms that looked interesting. I could tell that they were milkcaps from the unusual caps and the concentric circles. Turning one of them over I cut the gills with my fingernail and, sure enough, the gills produced milk. I don’t know what the species is.

The ants were still active, with quite a lot of interaction going on. I wonder what role fungi play in the structure of certain ant hills. Ants have been found to cultivate fungi gardens inside their nests, and there must be other ways that ants mix with the fungal kingdom.

This walk was on the edge of the moorland, passing down into a wooded river valley known as the East Dartmoor Woods and Heaths.

The woodlands that made up some of the best parts of the walk are known as Atlantic Rainforest. Their main tree species are oak and hazel. I’m not sure if ash was more prominent before ash dieback came into effect. This type of woodland is very uncommon with a lot of it being lost down the centuries. It is a special habitat for its plants, lichens, fungi and other wildlife. It’s very mossy and ferny.

It did not disappoint. This blackening waxcap was growing in moss on a woodbank. It is a stunning fungus when in this condition and in this light. I always associate waxcaps with grassland so often forget they can also be found in the woods.

Close by were these white spindles (I think), another sign to me of an ecologically rich and diverse woodland.

The autumn rains had the river swelled and running fast. You can see the brown of the peat-inflected water.

There is someone who has commented several times on this blog asking how or when to find honey fungus. If you’re reading this now, honey fungus is fruiting en masse at the moment. They are very photogenic indeed in the early stages, like the cartoony image of what a mushroom should be.

This fanned cluster of bracket fungi is probably turkeytail. These types of fungi can be found all year round but they look their best, like other mushrooms, in the October-November period.

I can’t claim to have found these lovely bonnets growing from some moss on a tree. I’m not sure of the species.

Here’s a snapshot of this beautiful woodland with an understory of bracken, and a tiny bit of hazel.

I’m not entirely sure but I think this is purple jellydisc. There is an organism on the birch leaf next to them which may be a fungus but could also be a slime mould.

On this walk we encountered one of the most beautiful mushrooms I’ve ever seen. This rainbow-coloured mushroom is a bitter beech bolete. It took the breath away. This was a phone pic as my camera wasn’t that happy about how dark it was. Well done Fairphone!

As mentioned in the first part of this blog trilogy, sulphur tuft is a very common mushroom. This was a nice spread. I haven’t spent any time looking to identify the other tufts, but I’m pretty sure this is sulphur.

The broadleaved rainforest was replaced on the other side of the river by coniferous plantation. The Woodland Trust owns this woodland and there was clear evidence of shifting it to its more species-rich habitat of broadleaved woodland. The walk followed part of the Dartmoor Way.

This bolete was helpful in leading us on the way along the track. Yet another bolete or relative growing from a mossy bank.

When I see a mushroom like this, I usually say to myself ‘macrolepiota‘, and leave it at that. It looks like a parasol relative of some kind.

This gorgeous little red mushroom was growing from the exposed soil of the trackway. This isn’t a mushroom I can remember seeing before.

Now here is one I have managed to identify. These tiny red-orange mushrooms were growing from the same habitat as the unknown species before. These beauties are goblet waxcaps, looking like they’re standing on the threshhold.

The walk left the woods behind and broke out onto Dartmoor proper with its famous granite tors and expansive views.

Haytor Rocks silhouetted against the wild skies often seen over Dartmoor.

Though the woods had been left behind, there was one final surprise as we descended through the farmland and hedgerows towards the National Park’s edge.

A tractor had been through to cut the hedges and road verges. In the process it had pulled up this stinkhorn mushroom. It wasn’t something you could miss. That was probably enough mushrooms for one day.

Thanks for reading. Safe journey.

Next week – part three!

Recent posts

Along the South Downs from Washington to Bramber

This is a long post with a lot of South Downs history in it. There’s history here you can touch that dates back over 1000 years.

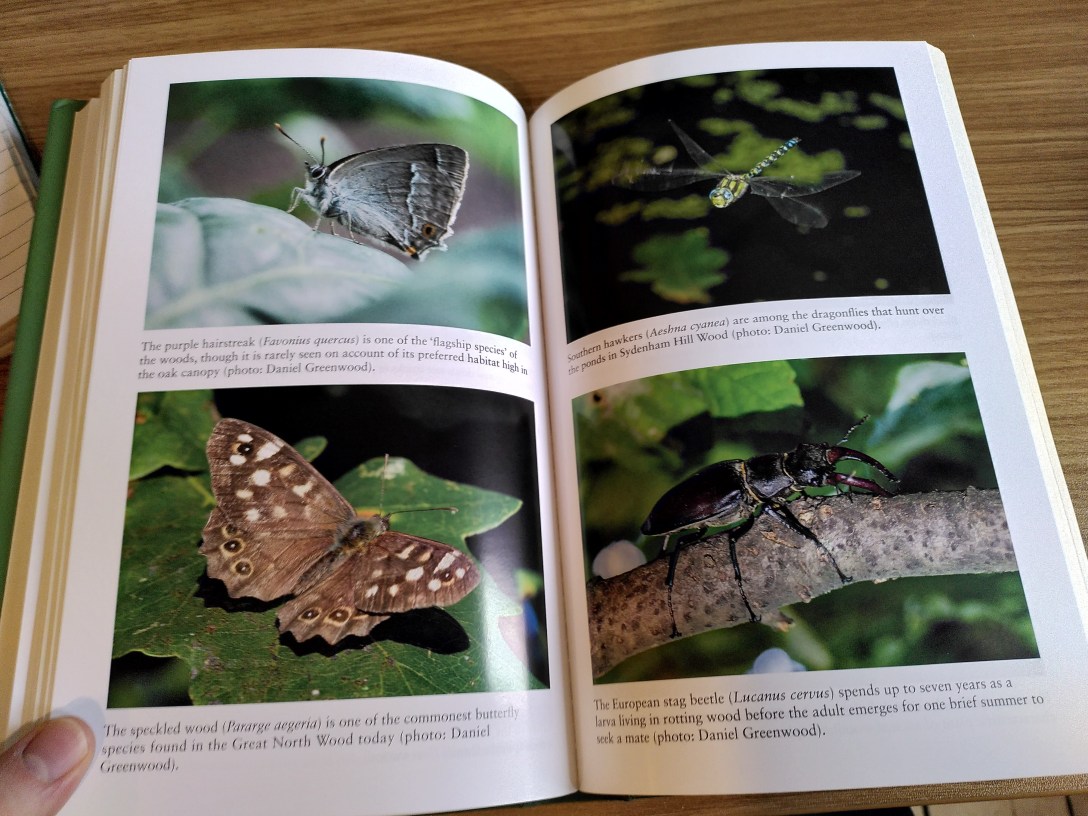

Fool’s Wood – my third poetry collection

Fool’s Wood is my third collection after I am living with the animals (2014), and Sumptuous beasts (2018).

November 2025: beware of pity

I’ve had a burst of American visitors in recent days (to my blog, not my house). So thanks for visiting, y’all, and sorry about the year you’ve had. You may have noticed I’ve slipped to monthly posts on here. Between April and October I posted blogs every Monday without pause, which is a tricky task…