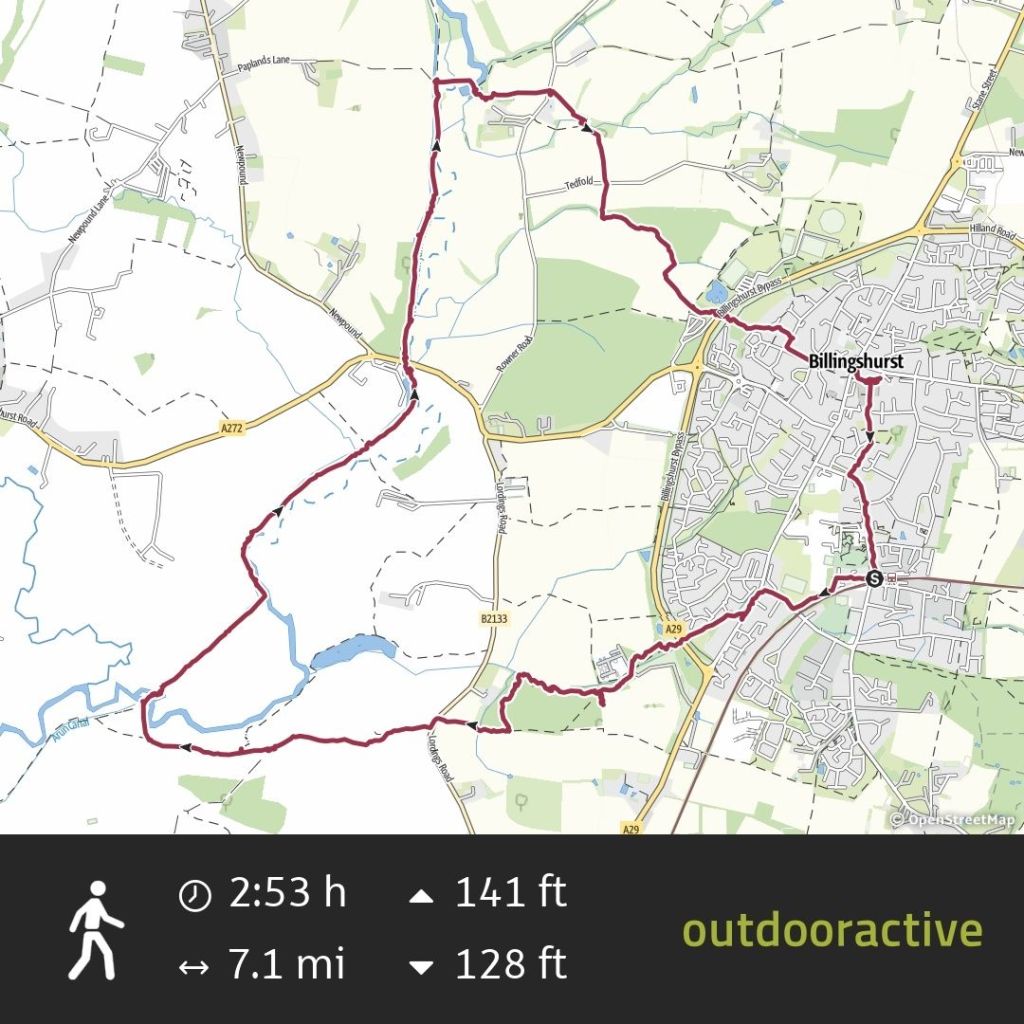

Billingshurst and the Wey-and-Arun Canal, West Sussex, January 2024

Pre-ramble

This long post (2500 words) is based on the Billingshurst walking route available in the Ordnance Survey guide to walks in West Sussex and the South Downs.

The difference in my route is that I went by train not by car. It’s always better by train if you can do that. I also took a longer route to the south via Parbrook.

Billingshurst is a growing ‘village’ on the from Victoria to Bognor Regis or Chichester.

The name Billingshurst means a wooded hill of the Billa’s people who were perhaps an extended family rather than a large tribe.

Billingshurst Local History Society

For this post I’ve relied on Geoffrey Lawes’ Billingshurst Heritage (2017) for historical references, which I borrowed from my local West Sussex library.

I wouldn’t do the walk after high levels of rain in winter because the Arun is prone to flooding in epic fashion and could make some of the walk impassable, particularly beyond the bridge.

This would be a good one to do in the spring when it’s a bit drier and the birds and woodland flowers are coming to life again.

There are some quite dangerous crossings here, so care needs to be taken when you meet the A29 twice, and another country lane that has poor visibility about a quarter of the way in.

Parbrook

After leaving Billingshurst station you pass through a new housing development to the west of the village, and then the village of Parbrook, which was once separate. There’s an impressive timber-framed building here called Great Grooms, which dates to the 1500s. It’s on the Historic English register as the Jennie Wren Restaurant, as it was recently known.

In Billingshurst’s Heritage there’s an insight into the life of people here around the time of the First World War. Doris Garton describes her childhood in a ‘small, primitive cottage’ in Parbrook, and her father’s life after he returned from the war:

In the 1920s my father did contract to local farms at Parbrook. He would set off at 6:30am with his tools and hay knife strapped on his bicycle. According to the seasons he did hay cutting and tying, harvesting and threshing, thatching and land work, draining, ditching, ploughing with a horse, hedge-cutting and layering of hedges. He was also sometimes hired as a water diviner, using a hazel twig.

Billinghurst’s Heritage: Geoffrey Lawes, 2017: p. 255

The walk gets serious quite quickly as you cross the A29, which is a diversion from the straight line of Stane Street, a Roman Road that provided a route from London to Chichester. Crossing the A29 gives the immediate reward of this – the sort of place where Doris’s father would have plied his trades in the 1920s:

Ancient woodland

As you probably already know, ancient woodland is a sensitive habitat, so be careful not to trample wildflowers like bluebell and wood anemone in the spring (it’s hard!), and not to disturb ground-nesting birds (March-July). I noticed some bluebells were peeking from the leaf litter, which seems to be fairly normal for January in the last decade.

It was here that I spoke to a local woman about the walk I was doing and what the best route was. I’m always looking for tips.

The woods are surrounded by open farmland. The make-up here is typical managed ancient woodland of old – hazel understory with mature oak trees (otherwise known as ‘coppice with standards’). Mr. Garton’s bread and butter.

Holly is another element of this prehistoric mix. This isn’t meant to sound patronising but I think that sometimes too much holly can be removed from woodlands by well-meaning people who want to reduce shade for flowers to thrive. I understanding the motivation, but holly’s powers are subtle.

Speaking of which, this magnificent holly was growing on one of the wood banks. I think it’s one of the largest I’ve ever encountered, probably around 200-300 years old, but I’m not sure.

I got a bit lost here and ended up following a desire-line (an informal path) along the edge of this stream, as you can see on the map above. The erosion of the bank (possibly by people and pets entering it) may have contributed to this hazel losing its footing and falling in. It does look quite dead.

This was my first time on the Sussex Diamond Way!

Having found the path again, I passed through this lopsided gate into the field.

There were some lovely large oaks along the boundary of field and woodland.

This is The Lordings, a Grade II-listed farmhouse dating to the 1600s (Historic England listing). With its uneven development and attached Sussex barn on the left-hand side, I had wondered how old it was. The windows of the house are in different places and rather small, which did suggest old age. The ditch in the image is part of a stream and pond. The landscape was lovely here, formed by the movement of water over time, which makes me think that’s a natural spring-fed watercourse. Little Lordings Wood sits nearby, and once upon a time woodland will have covered this entire area. ‘Lordings’ appears throughout this walk but I can’t find any more information about the significance of the name.

Now came one of the most dangerous crossings I’ve encountered during my 15 years of rambling (with my legs). The gate opens right out onto a road where the speed limit is 60mph, and you have no way of seeing what’s coming round the corner, or it seeing you. Having a hi-vis is useful in this kind of situation. Reader, I made it.

There are a number of old farm houses dotted around this walk. This is Tanners Farm, which ties in nicely with the oaks. Tanning is the job of removing moisture from animal hides in the process of producing leather. Soaking the hides in with oak bark releases the tannins from the bark and helps to waterproof the resulting leather.

It had the feel of an ancient agricultural landscape, with oak a core part of its progress over time.

The Tanners Farm section, passing beyond two large oaks, provides the best views of the entire walk. It was misty when I was there, so the views of the Downs weren’t complete. The drama is still felt, and is a reminder that one of the nicest things about walking in the Low Weald are the views of that majestic chalk whaleback.

This enticing path into oak woodland was not to be taken on this occasion.

The misty view south, with the Downs not quite making it into the scene. Another one for a spring or summer day.

So much choice. It was time to leave the Sussex Diamond Way and join the Wey-South Path.

The Wey & Arun Canal

January is too early for blackthorn, though that is changing with the march of climate change. This froth of white is actually lichen hanging over the Wey & Arun Canal.

The canal was constructed after plans were brought to Parliament all the way back in 1641 to ‘link the upper reaches of the River Wey to those of the Arun by a canal between Cranleigh and Dunsfold’:

[I]n 1785 The Arun Navigation Act was passed and the section between Pallingham and Newbridge opened two years later.

Billinghurst’s Heritage: Geoffrey Lawes, 2017, p.174

The canal began to transfer goods in 1816 when the Wey & Arun Junction Canal opened. So it took the best part of 200 years for the canal to be built (sounds like HS2). The Industrial Revolution of the 1790s changed the world in that time, but the impacts only really began to be felt a couple of decades after the 1820s when the canal was in full operation. It closed in 1888 – two centuries of planning, sixty years of action.

I passed these dead oak trees covered in an orange algae (I presume). I expect oak would have been one of the resources transported up and down the canal. The oak woodlands around Billingshurst, which covered a far greater area then, would have been felled, debarked and planked, their produce taken upstream to the Thames’ shipyards, or south to the Solent in Hampshire where international trade could have taken place. My understanding of the specifics is limited, so I’m generalising a bit, but Lawes States that most trade ‘was from London, mainly coal and groceries, porter beer and pottery’ (Lawes, p. 176). Lawes also confirms that the canal gave access to Littlehampton, Portsmouth, Chichester and Arundel via other water-links that could connect with the Wey & Arun Canal.

Ash trees would have been useful also, particularly for tool handles. One way to identify a distant ash tree in wet winter weather is the yellow glow on the outermost branches. These are xanthoria or sunburst lichens which of course thrive in wet weather. I would say this was a significant ash tree, and possibly had been pollarded, due to the branching taking place so low down on the trunk.

The Arun mocks the canal with its swooping bends as it takes its wild course through the outskirts of Billingshurst. The walk along this stretch was a sloshy trudge for a good while (wellies are advisable). It would be nicer in spring or summer, as all good walking guides will tell you.

The damp atmosphere around the river and canal meant the fingerposts have become home to algae, moss and lichen.

This is a large ash tree with what looks like an old hedgeline queueing behind it. To the right-hand side is what seems to be an alder, a tree that thrives in wet conditions. You can see a vehicle passing on the far left-hand side of the screen. The view of this field completely underwater during twilight is one of the more memorable scenes I can recall from travelling to Midhurst on the A272 over the years.

I passed this massive oak (it looks smaller in this image than it is in real life) several days a week between 2018 and 2022. The mud underneath is from the cattle standing there to shelter from the rain. The oak is probably around 400 years old, making this stretch of the Wey-South Path around Billingshurst a land of giants.

New Bridge only allows one car at a time, but I’d never seen the three frogs under the bridge until I did this walk.

This frog looked particularly surprised to see me.

In Billinghurst’s Heritage there’s a passage from a canal tourist in 1869 – J. B. Dashwood. He travelled along the Wey & Arun Canal one spring or summer from the Thames to the Solent. There’s a description of what our man J. B. saw with his travelling partner somewhere along this stretch. Quoted below.

At a little before 7 o’clock we reached Newbridge where our boat lay quietly at her moorings, wet with the morning bath of dew…[at the first lock] we watched the lock-keeper’s wife and two pretty daughters making butter in the early morning. Though flat the meadows on either side presented such a lovely English picture with cattle dotted about, …the larks sang aloft sending forth their melodious morning song and the banks of the Canal clothed with wild flowers of every hue and colour that we enjoyed this part of our journey almost as much as any.

Lawes, 2017, p.175

I wonder if these are the water meadows being described. While searching online for more information about New Bridge I discovered plans for housing affecting the area you can see in this image on the left-hand side (northern side) of the road. There’s a beautiful timber-framed house and barn called Hole Cottage (Historic England listing), dating to the 1500s. It wouldn’t be affected directly by the housing, the arable fields out of view towards the ‘village’ would be.

The proposal is called Newbridge Park (there’s a consultation online which closed in January). This area would become a country park, which is wise. Driving along the A272, the sight of the Arun flooding these meadows is a sight to behold. No one would seriously suggest building along this floodplain (would they?), particularly with the sort of winter deluges we’re getting now in this part of England. This is a rather old oak, perhaps 200 years, sitting at one of the bends in the Arun, which is just below the ground level.

This is that sumptuous bend in the Arun, a river which I have now learned was previously known as Tarrente or Trisanton which means ‘trespasser’ (Lawes, p.174). The river does trespass widely here, or is it the other way around? We have trespassed far into the floodplain of this great river. This is another view into the area which the developers propose would become a country park. But how long would that hold for, and who would fund the management of a park here?

There was a winterbourne (I am guessing) flowing over the banks and into the canal. Growing up in Lewisham in south London, it’s so nice to see water moving of its own accord in the landscape (with respect to the work to restore the rivers in that particular borough.)

Let’s appreciate the generosity of Eileen Cherriman here, who donated a stretch of the canal in memory of her husband John.

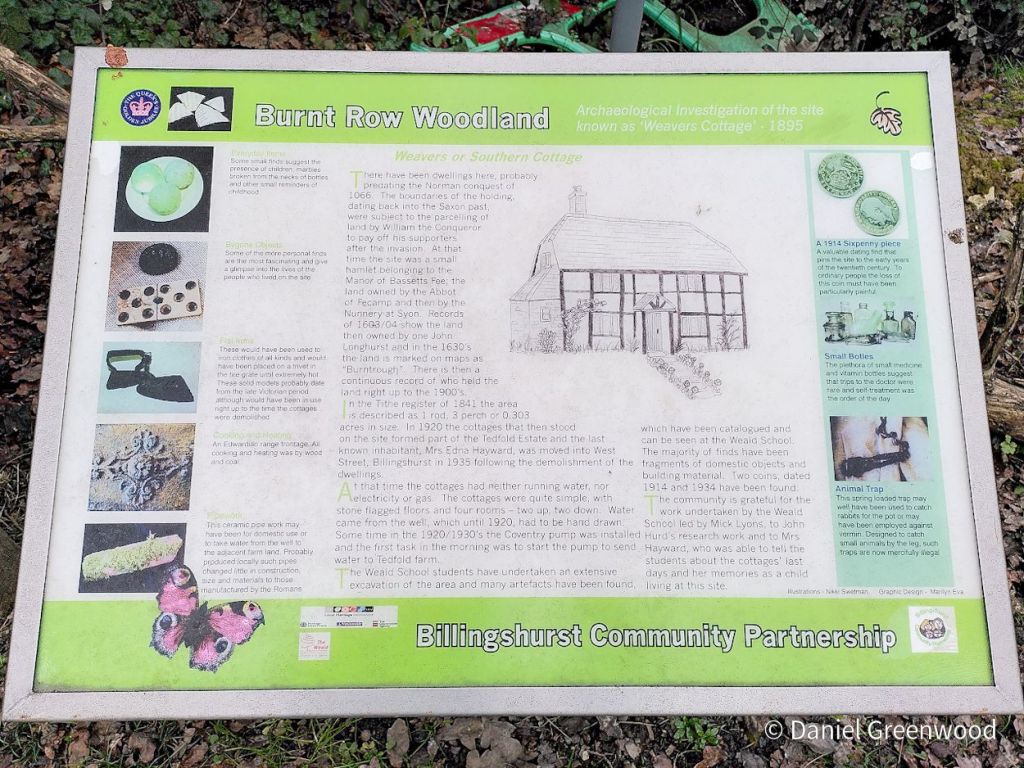

I do enjoy bringing interpretation boards to a wider audience.

Further down the canal is another bridge at Rowner Lock.

This was restored by the Wey & Arun Canal Trust.

Returning to Billingshurst

It was time to turn away from the watercourses and back towards civilisation.

The walk turns east as it returns towards Billingshurst through farmland walked by electricity pylons.

One of the footbridges on the way back was in a state of devastation, probably due to the impact of flooding. I presume this wasn’t vandalism, but from my experience you just can’t be sure sometimes.

A rather sickly oak in a process of retrenchment as the upper branches die away. You can see more oaks dotted around beyond the hedgerow.

Looking north-east into the Weald, with the mist spoiling most of the fun.

There are some interesting boards near the A29 crossing as you enter back into Billingshurst. I’m sorry that this timber-framer didn’t make it. This settlement seems to be very old, possibly prior to the Norman Conquest of 1066. Local school children have found lots of treasure at Burnt Row in their research into the site.

Entering back into Billingshurst I enjoyed the sight of this interesting timber-framer. A couple of local lads were causing a bit of bother here and couldn’t understand what I was doing.

I haven’t featured the church in this post though it is important and has a prominent position in the village. The Causeway is a row of houses, many of them old and timber-framed, with one potential dating back to the 1200s (Historic England listing). If you needed any evidence that Billingshurst and its surrounding countryside is an oaken land, this should be it.

Thanks for reading.