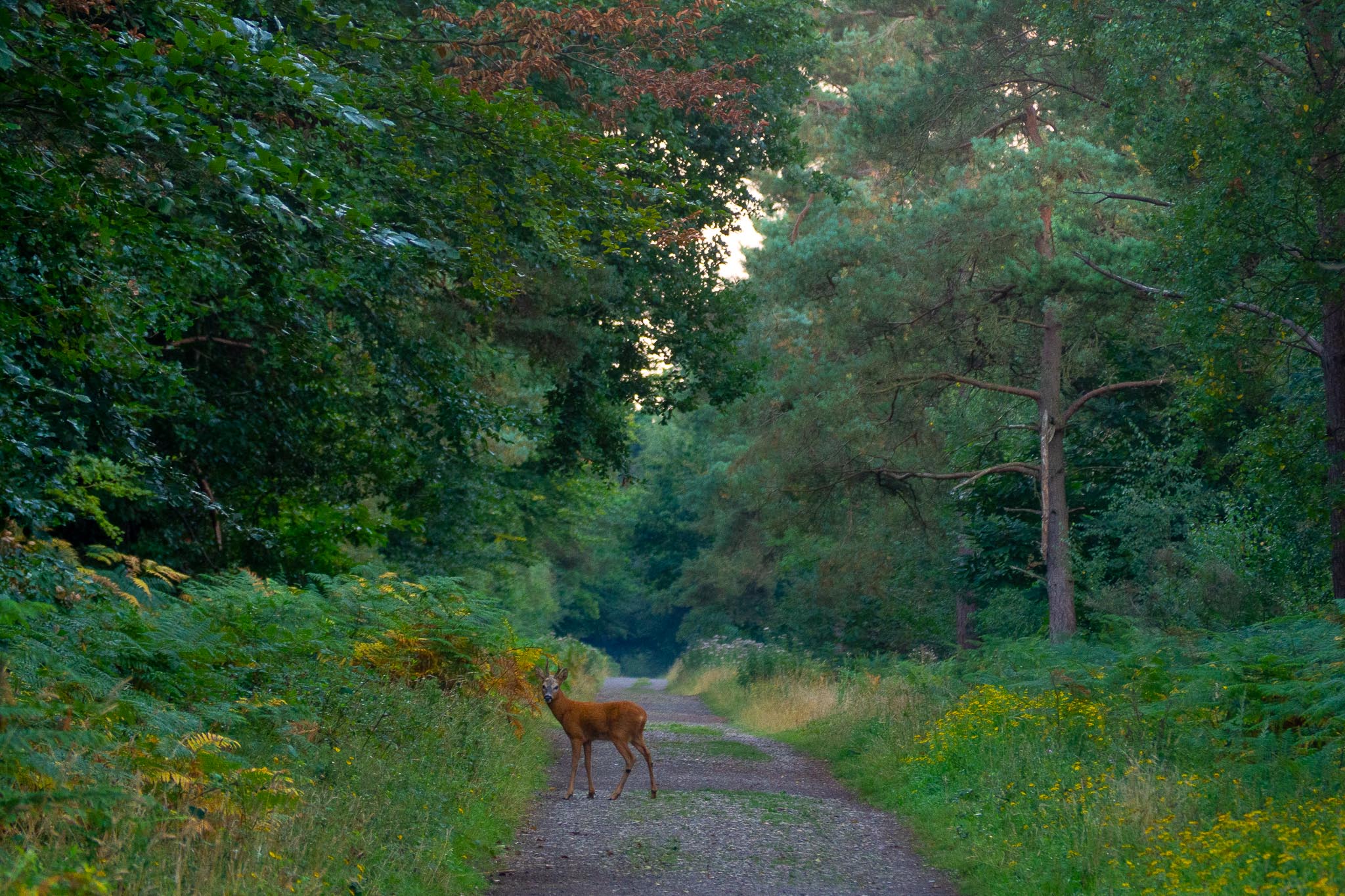

Warnham Local Nature Reserve, West Sussex, July 2024

I was making my first meaningful trip out to a wild space after being ill with Covid, to see if I could concentrate enough on taking some macro pics. Thankfully there were some very docile bugs pleading for their close up. Here you go, team.

I’ve missed a lot of the macro season this year, what has probably been one of the ‘worst’ summers in this part of England. Lots of rain, quite cool, clear lack of insects. I’m only just getting over brain fog so not able to compute how worrying the insect declines are right now. It seems that approving the use of bee-killing pesticides without appropriate risk assessment doesn’t help.

I was fortunate to spot this cinnamon bug nectaring in the flowerhead of a Michaelmas daisy within a few minutes of my visit to Warnham Local Nature Reserve. I love how this pollinating beetles get so covered by the pollen. It’s a bit like me after eating a choc ice.

Though flies are feared and reviled for their connections with unpleasant organic matter in this world, some of them are very interesting to look at. Many of them also tend to be pollinators. It’s not all about the bees. This fly is probably Nowickia ferox, which feeds on flowers. Moth fans – look away now. Their larvae develop in the dark arches moth.

Dock bugs are a common sight in southern England, especially in flowery grasslands and meadows. They are very easy to photograph – they’re like the mushrooms of the insect world, slow moving, if at all. How trusting.

Elsewhere, this mid-summer period is one of hoverflies, many which looked very similar to the untrained eye (this one) but which can be nice subjects among the flowers of hogweed and other umbellifers.

I was pleased with this photo of a dancefly as it nectared on some ailing hogweed flowers. That is one heck of a proboscis. The light is very soft and the background is a serene green.

Over the years (I’ve been using a dedicated macro lens since 2014) I’ve learned about species behaviour, and how a little bit of knowledge can really help you to find wildlife. In terms of invertebrates, I remember a blog written about fenceposts and how they were a good place to find roosting insects. This is solid advice.

During this visit, in the forefront of my mind was a past, failed attempt to photograph a robberfly where it sat on a handrail. On that same handrail I didn’t find a robberfly, but instead my mother and father-in-law, which was also nice. But, that wasn’t the end of the story…

Turning to head home, realising how fatigued I was, and lacking in normal, basic levels of energy, I spotted something. A robberfly was sat on a different handrail! It’s so pleasing to have this sense of validation for my fencepost knowledge.

In the world of wasps, we are of course in the throes of the UK Media Silly Season (despite there being a General Election, potential dictatorship in the US, and far-right riots across the UK!) and wasps are in the news. Interestingly the mwin story is, where are they?

iNaturalist users think the wasp above is a German wasp. What you can see is the wasp gathering wood shavings for a nest. But that wasn’t the only wasp I saw.

July and August are good months to see the iconic ichneumon wasps. I absolutely love them, an interest which was deepened by reading The Snoring Bird (I recommend it). I wasn’t fast enough for this ichneumon to really get a strong pic, but this will do.

Even worse was this attempt to photograph one of the Gasteruption ichneumons. People, I am just too short for plants that want to grow this tall. I do enjoy the bokeh here though (circular light in the background). Take that, full-frame cameras!

So, all in all a decent showing for a fatigued individual.

Thanks for reading.

Photos taken with Olympus EM1 Mark III and 60mm f2.8 macro lens, edited in Lightroom.