South Downs Way between Washington & Bramber (10 miles), West Sussex, January 2024

This is a long post with a lot of South Downs history in it that dates back over 1000 years. I wanted to call it ‘Peaks and troughs on the South Downs Way’ but that wouldn’t have done it justice.

This walk is from the first days of 2024 and has been in my mind ever since. It’s actually two years to the day (I love that stuff). The walk left me feeling ecstatic in the quiet way that walking can.

I completed the walk using public transport, with a bus to Washington and then a bus from Bramber to Pulborough, and the train from Pulborough. Planet saved.

The walk began by passing this excellent egg box.

From Washington I walked up to the pocked and scarred hills of Washington Chalk Pits, ghosts of old industry – much more of that to follow. This place is excellent for butterflies so it’s worth visiting in the summer months. The photo here is looking west towards Storrington and Amberley. Here a buzzard flew low over the hill, looking for prey among the chalk pits.

Far from being a place of wilderness, the South Downs have a deeply industrial feel to me. This is also because the views are so expansive you can see the stretch of human activity from miles away. This is the Rampion windfarm.

The windfarm needed a trench to be cut through the Downs when the electricity cables were routed north to the substation at Twineham. This image is from 2018 near Truleigh Hill showing the fresh, exposed chalk. The windfarm will be seen again on this eastward journey.

A man with a long beard had parked his tractor at the side of the South Downs Way where it approaches Chanctonbury Ring, and was breaking sticks from a fallen ash tree at the field boundary. Ash trees will pop up again along this journey.

The grass is always snooker table smooth where the beech trees of the ring come into view. I’ve posted before about a walk that heads south from here to Cissbury Ring, the site of another Iron Age fort. As I approached the Ring a herd of deer ran across ahead of me, leaping over the path.

Beyond the trees the metal orchids (aerials) of Truleigh Hill mark the South Downs Way some 10-15 miles east.

In isolation these windswept beech trees cross more gentle lines in the landscape.

The archetypal folds of the Downs, stubbled by trees and scrub.

Away from Chanctonbury a stonechat perched on a fencepost. These chats are your friends in the winter downland.

Looking down towards Steyning, the Adur had flooded. Why have these bales been left to grow mossy?

A tribute to one of the downland farmers, a sea of arable crop washing away to the horizon. The gleaming top right-hand corner of this photo is indeed the sea.

Beyond the crop a rupture in the chalk where the Shoreham cement works pipes up.

These wonderful fence posts are plopped into place by the rangers, the volunteers or the rights of way team from the National Park. The kindness of fingerposts.

The sheer openness of the Downs and its skies. The memories of these wide open spaces can stay with you for years, the very essence of why people deserve the right to pass along these ways.

Zooming in on Truleigh Hill – what is cloud, hill or perhaps even the sea? The eye plays tricks.

A memorial to two brothers who passed in their thirties and forties, replete with tinsel and flowers potted on either side. A Mini spinning by in the lane behind.

Another ghost of the Downs – an ash tree dying from the disease. One limb has fallen and more will follow in the winds. If you look closely you can see the remains of what are probably shaggy bracket fungi. Fear not, there is hope for ash trees in Britain.

Tilled fields, with Truleigh Hill edging closer, though it’s not part of this walk. The copse of beech trees is likely to shelter pheasants bred for shooting, a common economic activity in the South Downs, and not without its problems. Unfortunately it appears that the persecution of birds of prey (often linked to shooting estates) is rearing its head in the South Downs National Park.

Chalk flints clawed to the surface at the edge of some of the ploughed field the South Downs Way passes.

Peaks and troughs! One unmissable part of this walk (in many senses) is the pig farm right next to the South Downs Way. A man was piling up hay for the pigs and from a distance I heard him call one a ‘f***ing c**t’.

‘Really, us?’ they ask.

The windfarm once again comes into view with Lancing College, a boarding school, rising above the trees at the edge of the Downs. When I was a kid and misbehaving my parents would threaten to send me to boarding school. Now I realise they could never have afforded it! Bravo, mum.

I’ve reduced the exposure on this photo to bring out the mood in the sky. Another pheasant copse on the hilltop?

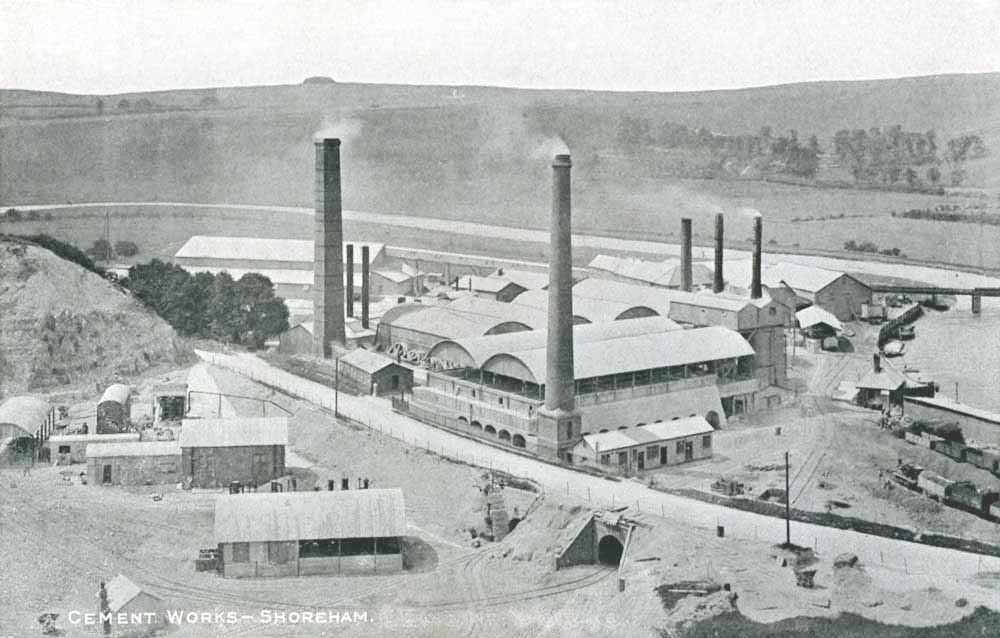

Shoreham cement works is built into the site of an old chalk quarry, which dates back to the 18th century. It’s on the market for housing as of October 2025.

This pre-1950s photo wasn’t one I took, but it shows the cement works before they were rebuilt into the Soviet-esque version currently standing. This article has a lot of interesting information and old photos looking at the history of the place.

St. Botolph’s Church is one of the oldest in Sussex, dating back to pre-Norman England. St. Botolph is a Saxon Saint associated with river crossings. The Sussex Parish Churches website points out that the village connected to the church ‘was an important port on the lower Adur until the sea receded after about 1350’. I enjoy the lichens growing on this old metal sign.

Dating from around 950, St Botolph’s was built near one of the first industrial trade routes in Britain, a Roman road along which tin was carried from the Cornish mines to the East Sussex seaport of Pevensey. Two thousand years on, and industry still stamps its mark in this book of rural West Sussex, with the railway line and modern cement works visible just a few hundred metres away.

Gail Simmons, Between the Chalk and the Sea: p.157

We’ll get to that railway line in a little bit, but after being out in the cold January air, it was nice to find a sheltered place to sit for a little while.

There’s a window that dates to the Saxon period at St. Botolph’s, which to me feels more mysterious than the much earlier Roman occupation (AD43-400). My guess would be the ’round-headed’ window in the top right here is the Saxon one, as per the official descriptions.

This should give a sense of the shape and colour of the interior. The nave and chancel also date to Saxon times.

The paintings at St. Botolph’s are subject to debate, and are hard to see. They could be part of an unproven ‘Lewes Group’ of wall paintings, with some potentially dating back to the 10th century (scroll down for more detail here).

St. Botolph’s is a magnificent little church with thousands of years of history packed into its flinty walls. You can see my church galleries here.

A helpful guide to what’s possible on the South Downs Way. I took the broken route to Bramber, having travelled the 7 miles from Washington.

Sheep-marked fields where the Downs rise again above the Adur, towards Truleigh Hill and then Devils Dyke.

An indicator of what is to come when you descend from the Downs into the Low Weald – oak trees. This was the only one I saw on this rather treeless walk. There should really be an owl in that trunk.

While the River Adur now wends its way through to Shoreham (the cement works chimney can be seen on the left-hand side) this is where the sea once swept. The river could be travelled by boat as far as Bramber, where my walk ended.

A small flock of swans roosting on the bank as the evening sun slips below the Downs. Another solitary ash tree survives here along the river. Over my shoulder the scene was far less tranquil:

The A283 is a major connecting road between the A24 and Shoreham where it joins the A27, the road that roars at the feet of the Downs for many miles.

The path through the wet grassland to Bramber. It amazes me to think the sea once reached this far. But that’s not the only ghostly presence haunting these marshes.

More recently this was the course of the Steyning Line, a railway now converted to an accessible walking and cycling path between Guildford and Shoreham. I was surprised to read that railway enthusiasts want to bring this line back. But for a photo caption, the article includes no mention of the fact this is now the Downslink path, one of the only truly safe long-distance walking and cycling routes in the area.

Bramber’s St. Nicholas Church as seen from the old railway path. The remnant wall above is one of the only remaining parts of Bramber Castle, with both the castle and church dating to the 11th century after the Norman Invasion of 1066. The castle has was a motte and bailey:

Bramber Castle was founded by William de Braose as a defensive and administrative centre for Bramber, one of the six administrative regions – each of which was controlled by a castle – into which Sussex was divided following the Norman Conquest. It was held almost continually by de Braose and his descendants from its foundation by 1073 until 1450.

Bramber Castle history webpage – English Heritage

At this point my camera battery ran out of steam, so I took a few final photos of Bramber on my Fairphone.

You can see how the raised position of the church and castle was chosen. The hills in the distance are the South Downs, to pass to the left (east) will take you to Truleigh Hill and eventually Devil’s Dyke. It’s believed Oliver Cromwell’s army set up guns on this hill during the English Civil War in 1642.

Bramber is a village of largely unspoilt brick and timber-framed buildings. I stopped off at the Bramber Hotel for a quick half before catching the bus, and encountered a wonderful oak timber-framed building.

St. Mary’s House dates back to the 12th century and is open to visitors during set periods. There’s also a tea room. There’s a nice write up of the history of the building on the St. Mary’s website, including the recent investment to bring it back to life.

Thanks for reading, it’s been a long journey.