I noticed some good news about ash trees recently and wanted to share my experience of a difficult decade for the European ash (Fraxinus excelsior, referred to here as ‘ash’), as well as some of the photos I’ve taken of this iconic tree. Working through this post, I’ve realised just how many images I’ve compiled down the years. I’ve also realised just how much I care about this tree as a species, and how painful it is to see it effectively being erased from the landscape by disease.

Ash is one of the first tree species that I really began to notice and tried to understand ecologically and culturally. When I started to take notice of wild trees, I saw that ash was everywhere in south London, seeding in railway sidings, parks, gardens, and woods. I’ve cut them down (not particularly big ones), planted them, pollarded them, photographed them and breathed their oxygen (obviously most people in the UK have!).

What do ash trees mean to people?

I’d like to start overseas, as ash dieback is Europe-wide problem.

This week it was 14 years since I visited Los Picos de Europe (The Peaks of Europe National Park) in Asturias, Northern Spain as a volunteer.

The photo above came up in my ‘memories’ and it was only then that I remembered the ash trees. This was a remote village high in the mountains where people were making cheese (they didn’t want the name of the village to be shared online). The ash trees here are pollards, with the branches cut back to make a single stick of a trunk. It’s probably severe enough to be considered ‘shredding’, which Oliver Rackham wrote about.

The reason this is done is to provide food for sheep – the fresh green growth of new ash leaves, which they love.

Interestingly, it’s similar in the Yorkshire Dales, where ash trees are abundant (see above and header image) and so are sheep. During one holiday in the Dales, I remember seeing a sheep climbing up a wall in order to nibble the leaves of an ash. What is also interesting to me, is that this is the same model of livestock grazing which spread from the Middle East, across Europe and into Britain thousands of years ago. It doesn’t sound dissimilar to the spread of ash dieback.

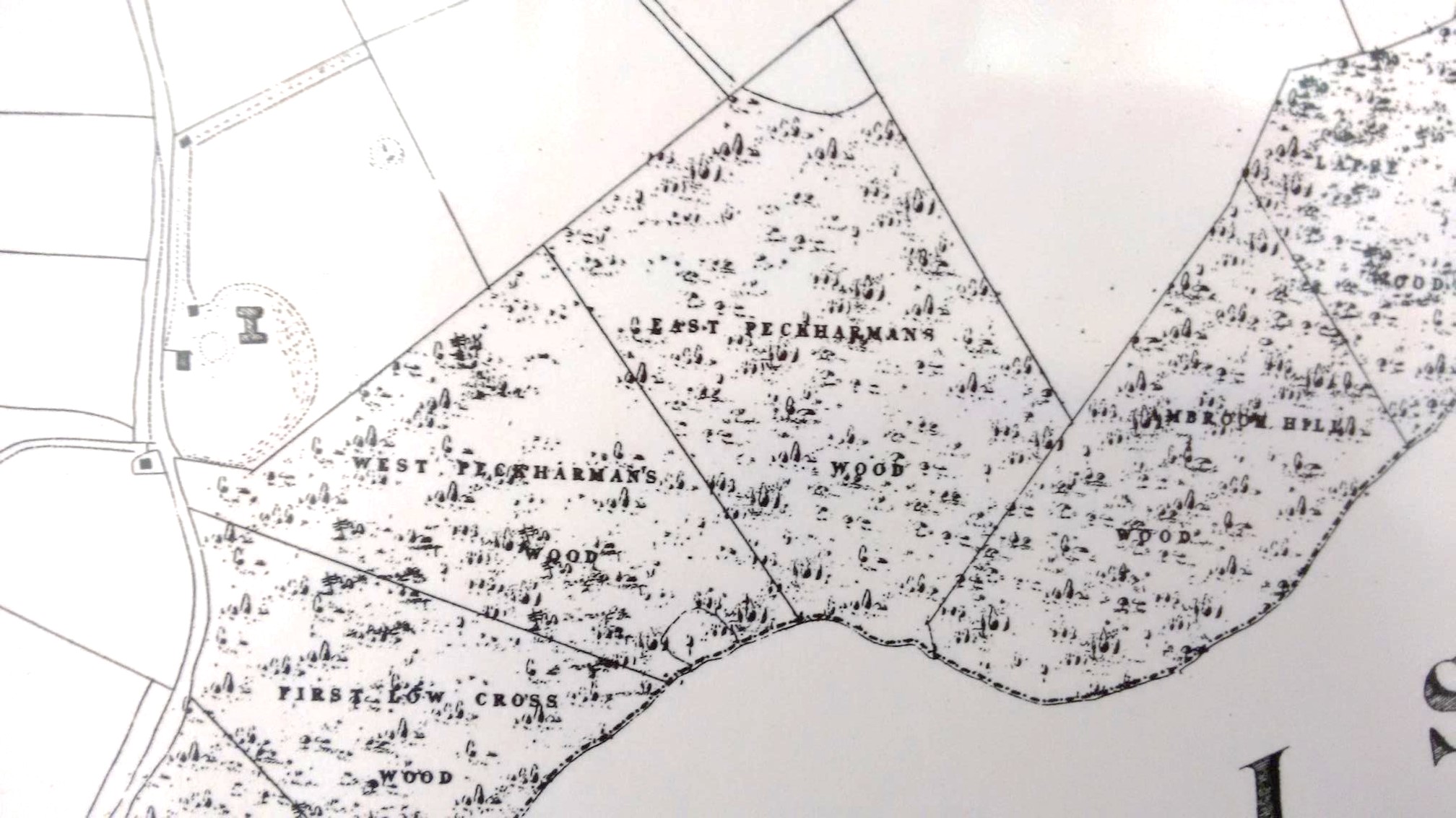

It’s not uncommon to see very large ash stools (old trees that have been regularly felled for timber) in boundary lines in places like Yorkshire, Sussex and Kent. I’m sure their coppicing was probably to provide ample feed to sheep, as in Northern Spain, above.

This mammoth ash in Dartmoor National Park in Devon is possibly the biggest I’ve ever seen.

What do ash trees mean to wildlife?

The fungus King Alfred’s Cakes has benefited in the short-term from an explosion in dead ash wood to colonise. The longer-term picture for fungi and lichen is not so good. Ash has a number of lichens that depend on it in places like the Lake District (my knowledge doesn’t extend very far here) which needs living trees.

Ash benefits ancient woodland flowers that arrive early in spring because the leaves are compound (they have leaflets, not broad leaves) and allow light into the woodland floor. Species like wood anemone and wild garlic do particularly well in their dappled early spring light.

I’ve encountered several ash down the years that have been for the chop on reasonable safety grounds in London, but then have been saved by the fact bats are living in them.

Bats can live under loose bark, in woodpecker holes (which are often found in older ash) and in large crevices. This magnificent ash was near Ullswater in the Lake District and had suffered what the tree officers would deem a catastrophic failure, but the woodland ecologists would be licking their lips at!

The Timeline

2012: when ash dieback arrived in Britain

One afternoon in the autumn of 2012 I was finishing my working day in the woods when I noticed the dying-back of an ash sapling. The stem had lesions and the leaves were drooping. It was my first year as a community woodland officer and ash tree seedlings were so numerous we actually had to pull them up in certain places. They were the epitome of a sometimes invasive British plant.

It was the first time I had seen a European ash tree (Fraxinus excelsior) infected with ash dieback disease, known scientifically as Hymenoscyphus fraxineus.

At the time we needed to report every new sighting to the Forestry Commission (as it was then), to help map the spread of this devastating disease. It spread so quickly that reporting became redundant, as were widespread protection measures. I remember someone remarking that asking people to clean their boots would be about as effective as asking the birds to clean their feet.

2017: ash dieback decimates the South Downs

It was only really when I moved to Sussex to work in the South Downs National Park that the real impact dawned on me.

During a walk with the South Downs Eastern Area Ranger team, I was taken aback by the way declining ash trees were opening up views of the coastal town of Eastbourne. It has continued to progress since then.

Groves of once green ash woodlands and verdant hedgerow trees were dying en masse. In the past few years trees along highways have been felled due to the threat to public safety from these brittle, dead trees overhanging roads, paths and properties.

The main concern is how the decay enters the heartwood (as above) and causes structural failure even within living trees, meaning the ash are more likely to fall unexpectedly. I spoke to a council tree officer who said that there have been a number of fatalities of tree workers due to ash trees. It’s tragic.

But how did ash dieback get to Britain? Fungi spread through spores, tiny particles that ‘seed’ in appropriate places and then grow into a living fungus that produces fruiting bodies. The fruiting bodies (mushrooms, to most people) then produce the spores. The ash dieback fungus is native to Asia, but there’s no way it could get to Europe alone. People helped it, accidentally, to arrive in Europe over 30 years ago. In Britain, it may have been helped by the process of growing UK saplings in Dutch hot houses, alongside infected ash saplings, and bringing them back to the UK.

2024: signs of resistance

This phone pic was taken in July 2025 when my local green space had been subject to ash removal. The logs show the scars of the disease (see previous) but the scene is not one of disaster. There are healthy ash trees on either side that are surviving and, indeed, thriving considering what they are up against.

That is something The Living Ash Project have been logging(!) – trees showing mild symptoms and overcoming the dieback.

This rather optimistic article highlights more of the positive steps, and advanced scientific interventions being made to save ash trees.

Ash trees in isolated areas, away from ash woodlands, may be in a much better position (literally) to survive the disease epidemic because they are not overwhelmed by spores from ash leaf litter found in thick leaf litter.

A turning point for ash trees?

The news for ash trees in 2025 is much more promising.

An article in The Guardian reports that ash trees in Britain are showing signs of evolving genetic strains of ash that will not succumb to the fungus. This means ash trees could return to the landscape in due course, though not in the same way.

In the south-east of England where I live the disease is said to have peaked.

Other research has shown that some isolated ash trees are surviving. I can vouch for this – there’s an ash tree in my mum’s garden (c.15 years old) in London that I’ve trimmed back once before. It is flourishing, so much so that the neighbours are asking for it to be cut down again. Welcome to London.

There is also a plea on the back of the latest research for woodlands to be allowed to regenerate on their own. Many people will be keen to point out the role of ‘rewilding’ in helping this process. In many cases it’s just a matter of leaving woodlands in certain places to do their thing, probably behind some fencing.

Here’s hoping that ash trees can be saved across Europe and wild trees are given the space to do their thing. In the end they may outlive us.

Thanks for reading.